Bruce Engel is the founder and principal of BE Design, a firm with offices in New York, USA, and Kigali, Rwanda. His work covers both East Africa and the New York region, including projects in New York City and Eastern Long Island. His connection to both regions is rooted in his life story. Bruce was born and raised in New York, and from 2010 to 2016, he lived in Rwanda where he worked on several nonprofit projects and taught at a local university. That experience made Rwanda feel like a second home. Even after returning to the U.S., he continues to travel back often, and many of his team members are based there, managing BE Design’s ongoing projects. At EliteX, we are proud to have Bruce Engel as part of the edition: 05 Visionary Architects Reshaping the Future of Architecture in 2025.

Bruce Engel | Founder & Principal | BE Design

Bruce always knew he wanted to be an architect. From a very young age, he enjoyed playing with blocks and building things. At the same time, he struggled with reading and writing because of dyslexia. While academics were not easy, architecture came naturally to him. He eventually studied architecture at Cornell University’s School of Architecture, Art and Planning. Though the program was demanding, it felt like something he had been preparing for all his life. He found joy in thinking spatially and creatively, and architecture became more than just a career – it became his way to connect with the world and contribute to society.

For Bruce, architecture is more than design and structure. It is about shaping lives and communities. He believes that architecture plays a major role in people’s daily experiences, as the built environment surrounds us almost all the time. He sees architecture as a powerful tool to bring about positive change. Whether it’s creating spaces for learning, living, or healing, he wants his work to improve people’s lives and the world around them. His commitment to architecture has always been steady, driven by passion and purpose. Growing up in a densely built city like New York inspired him. One quote that stayed with him was from the Finnish architect Alvar Aalto – that it is the role of the architect to give the world a more gentle form. His grandmother gave him that quote and called him her “gentle giant,” since Bruce is 6’5″ tall. That quote stayed on his desk throughout architecture school and continues to shape his approach today.

“I draw inspiration from the past – from local traditions and vernacular forms – to create architecture that serves today and lasts into the future.”

If Bruce had to summarize his design philosophy in one sentence, he would say: focus on the user, be inspired by the place, and design spaces that serve both the people and the environment for generations to come. His work is always rooted in the culture, history, and physical characteristics of a place. He aims to create architecture that not only looks good but feels good and lasts long.

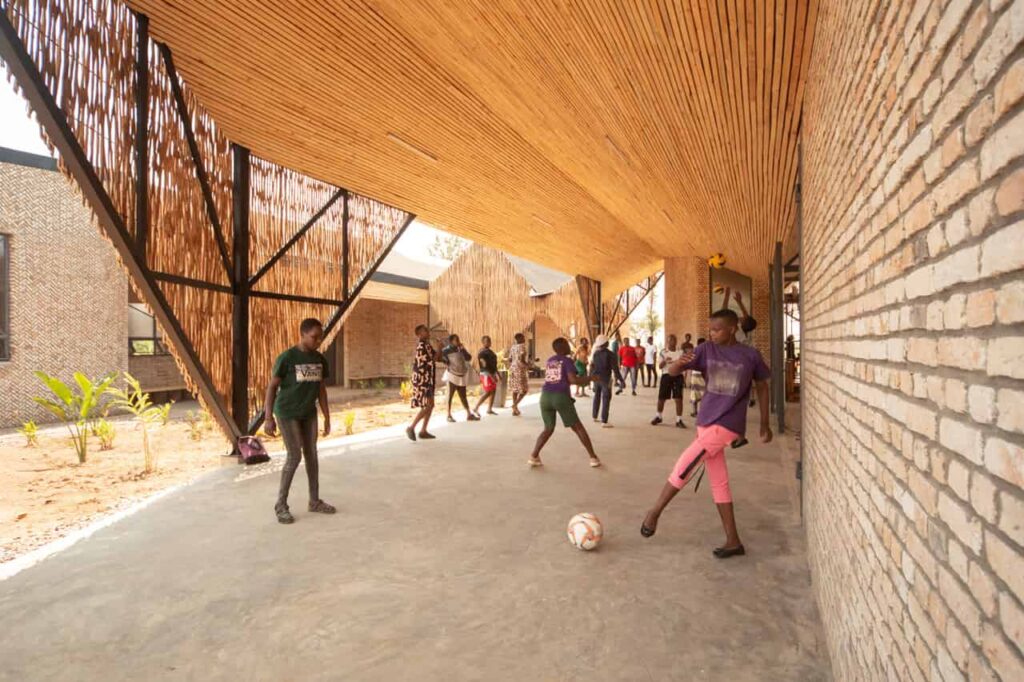

Bruce’s recent projects reflect this philosophy. In East Africa, many of his projects are for nonprofits, especially in education and community development. He has worked on schools, especially for young women in post-conflict countries like Rwanda. One organization he partnered with believes that by investing in women, you are also investing in the future of families and communities. These schools aim to provide not only education but also empowerment.

He has also worked on vocational schools and affordable housing near hospitals. These housing projects help both visiting doctors and local community members. His work in Rwanda includes teaching, too – Bruce was part of the team that helped launch the first school of architecture in the country. Some of his students later became interns at BE Design and are now full-time employees. He values the relationships he’s built through teaching and sees the success of his students as one of his proudest achievements. In New York, Bruce focuses mostly on residential projects. These private commissions help support the nonprofit work he does in Africa. Even in his U.S.-based work, he tries to push for sustainable design – using green technologies, minimizing energy use, and sourcing eco-friendly materials whenever possible.

Bruce’s approach to technology varies based on context. In East Africa, he keeps it simple. He believes that building systems need to be practical, durable, and easy to maintain, especially in places with limited resources. He often chooses local building techniques and materials to reduce costs and support the local economy. He sees this not just as a financial decision, but as a way to promote sustainability and community development. In the U.S., building codes often drive the use of newer technologies. Bruce uses these opportunities to go beyond the minimum standards and push for higher energy efficiency and better construction quality. Whether in the U.S. or Rwanda, his focus remains on long-lasting buildings that use appropriate materials and have a low carbon footprint.

One of Bruce’s biggest creative influences is vernacular architecture – the traditional building methods and styles that have developed over time in specific places. He draws inspiration from the local environment, climate, materials, and cultural practices that shape how people build and live. Whether it’s the type of stone used, the layout of a home, or how a roof handles rain and wind, Bruce believes there is much to learn from the past. He tries to reinterpret these traditions in modern ways, blending old wisdom with new technology to create meaningful architecture.

Looking ahead, Bruce believes that architects face big challenges. Climate change is one of the biggest. The construction industry has a major impact on carbon emissions, so architects must take their responsibility seriously. Bruce stresses the importance of using sustainable materials, reusing buildings when possible, and designing for long lifespans. He also believes architects should support local economies – by hiring local labor, sourcing local materials, and working with local craftspeople. In his view, the future of architecture lies in reconnecting with the past while addressing today’s urgent social and environmental needs.

“With great power comes great responsibility – architects have the power to shape the world, and they must use it wisely.”

When it comes to balancing function, innovation, and beauty, Bruce sees all three as deeply connected. He does not believe that beauty should exist without a purpose. For him, architecture is beautiful when it works well – when the design responds to the needs of the users, the site, and the environment. A successful project considers everything from local weather to how people live and interact. He aims to create spaces that feel natural, thoughtful, and responsible.

To young architects entering the field, Bruce offers a simple but powerful message. He recalls telling his students in Rwanda, referencing the Spiderman movie, “With great power comes great responsibility.” He believes architects have real power to shape the world – and with that power comes the duty to be socially, environmentally, and ethically responsible. He encourages young architects to stay true to their values and use their skills to make the world a better place.

When asked about his dream project, Bruce doesn’t name a specific building. Instead, he hopes to continue being surprised and inspired by the work that comes his way. He believes in putting good energy and effort into the world and trusting that meaningful opportunities will follow. What matters most to him is that his work continues to positively affect people, uplift communities, and leave behind structures that inspire future generations.

“Architecture can only be beautiful if it functions well – it must respond to people, place, and purpose.”

In both the quiet classrooms of Rwanda and the busy neighborhoods of Long Island, Bruce Engel’s architecture tells a story – one of care, connection, and hope. Through BE Design, he continues to shape spaces that serve people, honor place, and imagine a better world.